A guide to acidification

By Mary K. Foy

Features Barn ManagementA deeper dive into acid use in our water systems.

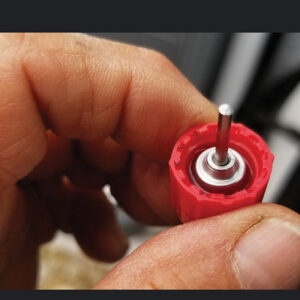

Organic acids can be a useful tool for bird health but when used improperly they can lead to issues like mould in the waterlines as shown here.

PHOTO CREDIT: Mary K. Foy

Organic acids can be a useful tool for bird health but when used improperly they can lead to issues like mould in the waterlines as shown here.

PHOTO CREDIT: Mary K. Foy We’ve all done it. We walk through the birds and notice the droppings are loose. So, we head back to the anteroom, mix up a stock solution of an acid and water and begin injecting it into the water system.

Maybe we heard another producer talking about how much more water their birds were consuming since dropping the pH in their water system to 5.5 and we decide to try it. Maybe we have acids sitting around to use just for cleaning the waterline when the barns are empty. At one time or another, we have all either used or contemplated using an acid product in our waterlines to improve either the performance of our birds or our equipment.

All these reasons for using an acid product are valid. However, we seldom dig too deep into which acid products we should use for what we are attempting to accomplish. Most of us use what we have on hand. That single misstep, though, can lead to months of trying to figure out why performance has suddenly dipped or why your drinkers have begun to leak, or where the heck that black gunk in the waterline came from.

If you’ve ever used an acid product in your water system or contemplated the choice of acid to use, stick with me as we dig a little deeper into what to use, when to use it and the consequences of misuse.

The first question that needs to be asked when contemplating the use of an acid in the water system is, “Why?” That question alone determines the kind of acid product to use for optimum benefit (and the least negative consequences).

Most acids can be put into two categories – organic and inorganic. The reason for wanting to use acid products will determine which of these categories to turn to for help. Generally, if producers are aiming for better bird health, they’ll want to use an organic acid. If the reason for using an acid product is to lower pH, they’ll want to use an inorganic acid. If they’re using it to clean waterlines, concentrate on its descaling abilities and use an oxidizer for organic buildup.

Organic acids

Misuse of organics acids can also lead to the development of vinegar slime as shown here.

PHOTO CREDIT: Mary K. Foy

Organic acids are carboxyl acids that contain a carbon-hydrogen bond. They are considered weak acids. Some of the common organic acids we add to the waterline are acetic acid (vinegar) and citric acid. Several studies have indicated that organic acids such as formic acid and propionic acid are effective at controlling E. coli and Salmonella in the gut, while acids such as lactic acid and butyric acid can promote beneficial Lactobacillus in the gut microflora.

Many times, these acids are included in feed formulations. When it comes to adding an organic acid to the waterline, the benefit may be more to aid the digestive enzymes and increase the intestinal mucosa, although gut health microflora may also benefit.

The drawbacks of using an organic acid can be contributed to that pesky carbon atom mentioned before. That carbon-hydrogen bond makes all the difference in what can happen in the waterline. The carbon atom in organic acids can be used by microbes as an energy source.

We like to take comfort in the thought that because we are lowering the pH we are killing all the microbes. We are not killing all the microbes. In fact, we may be creating the perfect environment to wind up with clogged drinkers. Multitudes of fungi, molds, and yeast thrive in extreme environments with a pH from two to nine.

In an acidic environment, some organisms can eliminate the positively charged protons that are present through a translocating efflux pump they have developed. Others protect themselves and adapt by changing their polymorphic growth to produce thicker cell walls.

Sometimes, we even get a compounding problem when fungi produce a secondary metabolite that is used to defend their habitat and suppress the growth of competing bacteria. This secondary metabolite can interfere with chlorination, further inhibiting our attempt to effectively treat our water.

Bacteria can also thrive in a low pH environment. Listeria monocytogenes, various Salmonella species, and E. coli have all been shown to adapt to living at a pH below 5.5. These organisms can be found in the litter, they are passed from bird to drinker, they come in on our shoes and they are pulled in through the ventilation system. They are waiting for us to provide the perfect environment for growth. The thought that we are eliminating all the microbes by lowering the pH can get us into more trouble than we had before using the organic acid in the first place.

Organic acids can be a useful tool for bird health, but it must be remembered that it is also a great source of energy for many fungi, yeasts, molds, and bacteria. Use it short-term and follow it with an oxidizing agent.

Inorganic acids

If your “why” is to lower pH, an inorganic acid should be your method of choice. These are sometimes referred to as “mineral acids”. Inorganic acids are considered stronger than organic acids and will be more effective at lowering pH while using less product. They do not contain the carbon-hydrogen bond present in organic acids and, therefore, the chance of drinker-clogging organisms using them as a food source is much lower.

The major drawback of inorganic acids is that they may be harsher on our drinker equipment (stainless steel, rubber). Certain strong acids can etch, pit or remove the protective chromium oxide layer of the stainless steel in our drinker systems. Unified Alloys of Canada states that different grades of stainless steel have different resistance to particular acids, but that the most damaging acids are hydrochloric acid and sulfuric acid, especially when mixed with a chloride compound (which we often do on the farm).

A chlorine/chloride-free phosphoric acid can often be a safer alternative. It’s a good idea to consult with the manufacturer of your drinker system to ask what they recommend for the type of stainless steel they use. Be aware, there are manufacturers that have warranty statements that read “continued exposure of the equipment to a pH below six and more than one ppm of chlorine will void any and all warranties on this equipment”.

Finally, let’s discuss using acids to clean waterlines when the facilities are empty. Inorganic acids are excellent for descaling waterlines to remove mineral buildup and scale. The pH should be four or slightly below and the inorganic acid does not need to be left in the waterline for long. The type of acid used will determine how long you can leave it. Again, consult the waterline manufacturer.

Organic acids are weak and are unreliable for removing biofilm. Several research studies have shown that once a polysaccharide biofilm has been produced, acid products have a difficult time breaking down the complex. A study at Auburn University revealed that an infectious laryngotracheitis vaccine (ILTV) administered through the waterline got caught up in the biofilm and was still being transmitted to the birds 21 days after initial administration.

Citric acid and sodium hypochlorite, separately, did not penetrate through the biofilm to kill the ILTV. The stronger oxidizing power of sodium bisulfate and hydrogen peroxide (also separately) did penetrate through the biofilm and inactivated the ILTV.

Acids are an extremely useful tool for us on the farm but only if we know why we are using them and what the difference is among them.

Mary K. Foy is the director of technical services for Proxy-Clean Products. The U.S. company’s cleaning solution is used in Canada as part of the Water Smart Program developed by Weeden Environments and Jefo Inc.

Print this page